Ida Tarbell, who tore into the Standard Oil monopoly, did not attend a journalism school. Nor did Lincoln Steffens — or any of the muckraking reporters of the Progressive Era who fueled political and social reform in the early 20th century.

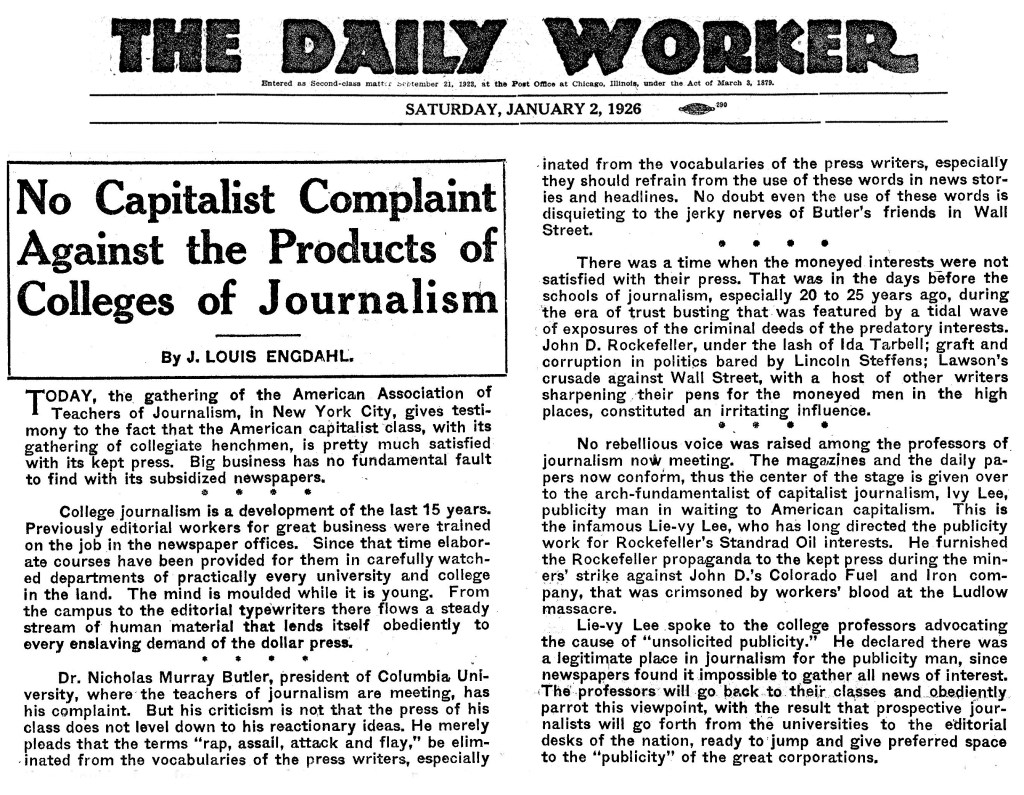

A century ago, the Daily Worker suggested journalism schools — the University of Missouri’s was first — were a reaction by “moneyed interests” to the exposés of capitalism’s failures by the muckraking press.

“There was a time when the moneyed interests were not satisfied with their press,” the Daily Worker said. “That was in the days before the schools of journalism, especially 20 to 25 years ago, during the era of trust busting that was featured by a tidal wave of exposures of the criminal deeds of the predatory interests.”

Instead of on-the-job training, the minds of future journalists were now being shaped in “elaborate courses … in carefully watched departments.” The result was a “kept press” unlikely to cause consternation on Wall Street.

“From the campus to the editor typewriters there flows a steady stream of human material that lends itself obediently to every enslaving demand of the dollar press,” John Louis Engdahl, an editor of the Communist Party organ, wrote in the Jan. 2, 1926 edition.

The Daily Worker was reacting to the recently concluded three-day meeting of the American Association of Teachers of Journalism in New York City, which, like most gatherings of journalists and academics, was replete with platitudinous pronouncements and banalities. (One accomplishment was the approval of a bold resolution urging newspapers to reduce the size of headlines “in accordance with canons of reasonable taste and sound proportion.”)

But Engdahl was also triggered by the organization giving Ivy L. Lee, publicity agent for John D. Rockefeller, a platform. Lee, who became notorious when he represented Rockefeller during the bitter Colorado coal strike that led to the Ludlow Massacre in 1914, spoke to the assembled journalism academics on the value of “unsolicited publicity.”

“Lie-vy Lee,” Engdahl wrote, was the “arch-fundamentalist of capitalist journalism.”

Rockefeller, it turns out, was not Lee’s dodgiest client.

In July 1934, Lee told a congressional committee he was paid $25,000 a year (equivalent to more than $600,000 in 2025) by German chemical giant IG Farben for advice on giving “Hitler’s Germany a better name in the United States.”

Lee, a St. Louis high school graduate (the original Central High, 1020 N. Grand), succumbed to a brain tumor four months later.