Several years ago, as I looked for coverage of a long-ago dairy show (I was helping a friend research a book), I spotted a brief article on page 4 of the Oct. 14, 1909 edition of The Missourian. It was a short report about a new campus organization.

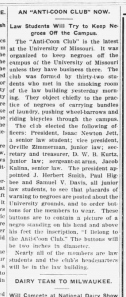

Here’s the lede:

The ‘Anti-Coon Club’ is the latest at the University of Missouri. It was organized to keep negroes off the campus of the University of Missouri unless they have business there. The club was formed by thirty-two students who met in the smoking room of the law building yesterday morning. They object chiefly to the practice of negroes of carrying bundles of laundry, pushing wheel-barrows and riding bicycles through the campus.

The article listed the organization’s officers. Their plans: to post warning placards on campus and produce buttons for members to wear. “These buttons are to contain a picture of a negro standing on his head and above his feet the inscription, ‘I Belong to the Anti-Coon Club.’”

I was unable to find subsequent coverage. So I don’t know if the organization gained followers or lasted beyond the announcement of its formation. But it wasn’t difficult to track most of the individuals associated with the group’s leadership.

Most alumni of the ‘Anti-Coon Club’ became practicing lawyers, according to an old university alumni directory.

Isaac Newton Jett, who was 34 at the time that The Missourian identified him as the club president, was a married preacher. After graduation, he became an elder in the Christian Church in Howell County, Mo., then a prosecuting attorney in West Plains. He left Missouri, and died in San Antonio in 1957.

Orville Zimmerman, elected vice president of the ‘Anti-Coon Club’ at age 29, became a lawyer in Kennett. He was elected to Congress as a Democrat in 1935 and served until his death in 1948. A powerful enemy of the Farm Security Administration’s efforts to stabilize the income of agricultural workers, he blamed agitators, unions and the press of misrepresenting the harsh conditions of rural life in the Bootheel. “A perversion of the real situation in southeast Missouri,” he said.

Other ‘Anti-Coon Club’ officers became lawyers who practiced in Columbia, Kirksville and Kansas City. One ended up in Seattle.

Tracking their careers may not seem like the most productive use of time. People engage in all sorts of foolish and irresponsible behavior in their lives. Those unfortunate actions may be the only ones ever memorialized in an obscure newspaper account. Their other deeds – good and bad, including their descent into old age and obscurity – rarely are noted, even in obituaries.

Moreover, what could one hope to discover that wasn’t already understood about those times? We know, for example, that racist views once had free rein in the institutions of our Republic – in our social lives, workplaces, literature and culture. And there’s also the question of relevance. Those law school students are long gone and largely forgotten. Today, the oldest living among us reached adulthood around the Second World War – and that’s usually where our contemporary accounts of the Civil Rights Movement begin. Desegregation of the military. Brown v. Board of Education. The Montgomery bus boycott. Birmingham. March on Washington. Selma. Memphis. Those events fit narratives about equality of opportunity; they don’t necessarily address the deeper questions of reparations, punishment and justice.

The value, though, of digging deeper is this: It’s possible, given the wealth of archival material now available, to rediscover pieces of our history that have been long forgotten or obscured by contemporary accounts – and to uncover links that could have eluded earlier researchers.

Anyone who’s searched through bound volumes or old microfilm recognizes how digital records have made research easier. It’s essential, though, to understand the limits of the newly accessible material. Newspaper accounts and official records are often riddled with errors. Verification takes multiple sources – and a broad knowledge of historical context. A wealth of material hasn’t been digitized; some of what is available has been privatized and comes at a price.

Still, for a population that’s understood its past mainly through the soft glow and filters of high school instruction and Hollywood, it’s a worthwhile exercise to revisit old stories told with all the detail and passion of first-hand accounts. At the very least, it deepens our understanding of contemporary grievances.

A recommendation: Search the archives of the historical St. Louis Post-Dispatch (free online to public library patrons), using just the keyword “lynching.”

Or as an alternative, search “Ferguson” and “Negro.” Find out, for example, why Grant Edwards, a barber and pastor, was fined $100 and sentenced to jail for six months back in 1915.

(Originally published Sept. 1, 2014)

you tell an interesting story. love knowing a thinker.