Remembering George Dinning, a Black farmer in the South who courageously defended his family from a white mob, then sued — and won. (First published on May 5, 2018)

FRANKLIN, Ky. — Late on the night of Jan. 21, 1897, a group of 25 armed white men showed up at the home of George and Mary Dinning and told the family they had 10 days to leave.* They accused George Dinning, a former slave, of stealing chickens and hogs.

Dinning insisted he was no thief, but these Night Riders weren’t listening. They shot into the house — most of the couple’s 12 terrified children were there — and hit Dinning in the arm and grazed his forehead.

Despite his wounds, Dinning returned fire, killing a 32-year-old man named Jodie Conn. After the whites fled, Dinning made his way to nearby Franklin — the county seat of Simpson County, Ky. — where he turned himself in to the sheriff.

The vigilantes, as Dinning had feared, returned to his home and on a bitterly cold night forced his wife and children to leave. They then plundered the

family’s possessions, and burned the house to the ground.

Initial newspaper accounts were unsympathetic to Dinning — The Courier-Journal of Louisville published a dispatch on Jan. 23 that described Dinning — his surname was misspelled as “Dunning” — as a “worthless and dangerous negro” while Conn, “a quiet, inoffensive man,” was a member of a family counted among “the oldest and wealthiest in this part of the state.”

Dinning likely would have been lynched, except that the sheriff of Franklin quickly packed him off to nearby Bowling Green and then to Louisville, about 140 miles north of Franklin.

When Dinning was put on trial in Franklin five months later, Gov. William O. Bradley ordered the militia to protect the jail. (Even then, the state guard was fired on by locals.)

Based on the testimony of the whites who’d been with Conn, Dinning was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to seven years of hard labor. But the case had aroused national indignation, especially in the northern press, which saw the attack on Dinning as part of a broader effort by whites in the South to “rid themselves of all the negroes” through intimidation and terror.

On July 17, 1897, after less than two weeks in prison, Dinning received a full pardon from Governor Bradley. The state’s first Republican governor, Bradley was an outspoken foe of racial violence. Just that year, he’d called a special session to push through an anti-lynching law.

In his order granting Dinning a full pardon, Bradley wrote in part: “He defended himself as every dictate of reason and humanity demanded and justified. In protecting himself he did no more than any other man would or should have done under the same circumstances.”

Upon his release, Dinning joined his family in Jeffersonville, Ind. — across the Ohio from Louisville — and began speaking out about the injustice he had endured, even telling a local paper that he intended to file a damage suit against the men who burned his house. Talk like that was intolerable to many whites, and on Sept. 22, 1897, Dinning was attacked by three whites who gouged out his right eye and battered his head “into a mass of blood and bones.”

Poor, illiterate George Dinning then made good on his promise: he sued the white men who drove him from his home. And to press his case, he turned to one of the most prominent lawyers in Kentucky: Bennett H. Young, a Confederate hero who rode with Gen John Hunt Morgan and later led the raid on St. Albans, Vermont. **

Legally, it was a straightforward case: Witnesses who testified in the earlier criminal case against Dinning succeeded in implicating themselves in the mob action — leaving no doubt about their involvement. Still, to prevail, Dinning would have to overcome the deeply ingrained racism of the time. (Just three years earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of racial segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson.)

At the federal court trial in Louisville, Young rose to the occasion, giving what the St. Louis Post-Dispatch characterized as “a speech rarely equaled for passionate earnestness.” The newspaper quoted excerpts at length:

“There was great rejoicing in hell this morning. When men of the intelligence, the high standing and brilliant talents of the two lawyers who have spoken for the defendants in this case stand in a court of justice and condone assassination and argue that practically a man may be murdered or driven from his home and his family by any self-constituted mob that may elect to take his life and destroy his property, all the demons smiled and applauded. Well may we, in view of the brutality towards this man and his wife and children, as detailed from the witnesses, cry out, ‘Is God dead?’”

Young denounced the “whitecaps and kuklux” who drove Dinning from his home: “If they be fair representations of the present type of man Kentucky is producing we must confess that we are degenerate sons of noble sires.”

On May 5, 1899, a jury of 12 white men returned a verdict of $50,000 in Dinning’s favor against six members of the mob, including the estate of Jodie Conn. The sum, which included punitive damages, is roughly equivalent to $1.4 million today.

The verdict was, given the times, remarkable. The Picayune of New Orleans reported: “The outcome is regarded as sensational, indicating an entirely new method of dealing with and punishing lawless mobs that have been so numerous in the south.” The Twin Cities American of Minneapolis said the “verdict partly redeems the South from its heavy burden of disgrace and barbarism.”

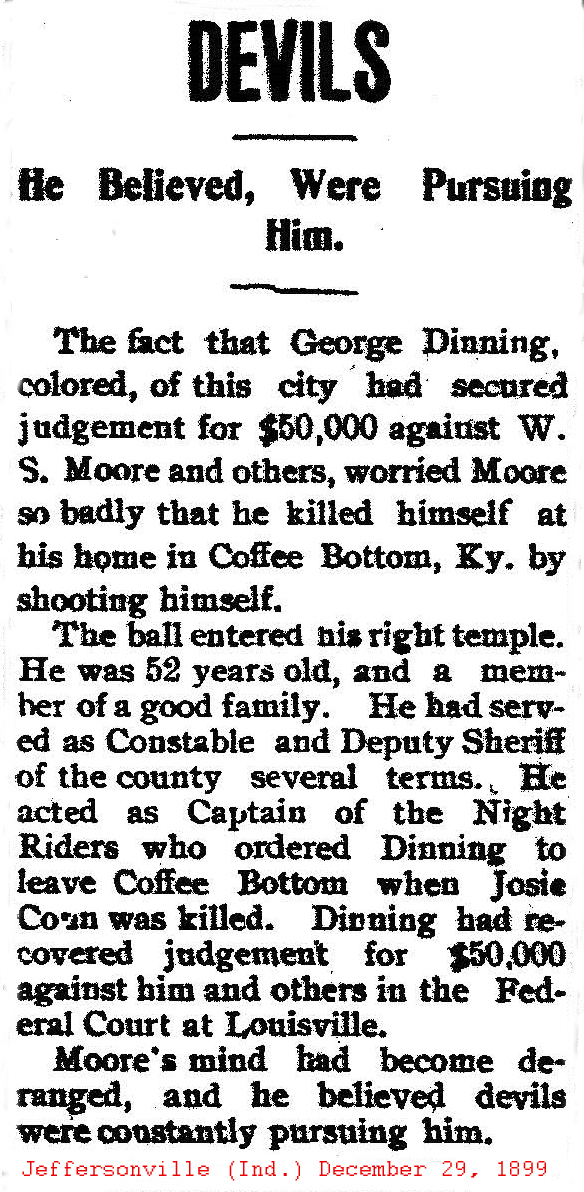

W.S. Moore, one of the defendants who led the mob that attacked the Dinning property, was said to be so unsettled by the verdict that he committed suicide at his Coffee Bottom, Ky., home on Dec. 21, 1899.

Dinning never collected $50,000, and settled for just $500 nearly three years after the verdict, according to newspaper accounts in 1902. (Simpson County, Ky., Historical Society records say Dinning ultimately recovered $1,750 — still much less than the original judgment.)

Dinning eventually drifted into obscurity — his surname changed in public records to “Denning.” While Bennett Young continued to give speeches about the glories of the Confederacy, Dinning appears to have been employed as a laborer and driver for a local coal supplier, city directories show. Young died in 1919, and was buried in Louisville’s Cave Hill Cemetery. George Dinning died in 1930 at about the age of 73; Mollie (or Mary) died in 1944 at 79 or 80. Both are buried in the Eastern Cemetery in Jeffersonville. — (First published on May 28, 2017; revised on May 5, 2018. © 2017 Roland Klose. All rights reserved.)

P.S. Historian George C. Wright included part of Dinning’s story in an examination of racial violence in Kentucky, published in 1990. The Associated Press, in 2001, included part of Dinning’s story in a larger series that examined how Black farmers were driven off their land. The AP found that the 124-acre farm that Dinning was forced to relinquish, which had been broken into smaller lots, had a total assessed valuation of nearly $250,000.

As was the case in many counties visited by white terror, the population of African Americans declined. In 1880, 2,797 residents, or 26 percent, of the 10,641 residents of Simpson County, Kentucky, were Black, according to the U.S. Census. In 1900 — three years after the Dinning family was driven out — 2,550 residents, or nearly 22 percent, of the 11,624 residents were Black. In 2010, that number was down to 1,827, or 10.5 percent, of 17,327.

In 2021, Little, Brown and Co. released “A Shot in the Moonlight,” Ben Montgomery’s detailed retelling of George Dinning’s story, including extensive testimony from both the 1897 murder trial in Simpson County and subsequent civil suit in federal court in Louisville.

________

* Some accounts incorrectly have reported the date as Jan. 27, 1897.

** Few men did more to advance the Lost Cause mythology of the South than Bennett H. Young. After the war, he wrote “Confederate Wizards of the Saddle,” a 630-page paean to the Confederate horsemen like Memphis, Tenn., slave-dealer Nathan Bedford Forrest. And as commander-in-chief of the United Confederate Veterans Association, he worked with allied groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy to pepper the nation with monuments to the CSA. His crowning achievement as a Confederate apologist — though he didn’t live to see it completed — was the 351-foot obelisk at the birthplace of Jefferson Davis in Fairview, Kentucky. Young helped acquire a portion of the farm where Davis was born, then led the fundraising effort to build a monument like the one honoring George Washington.*** Young also was the featured speaker at the 1914 dedication of the Confederate memorial in St. Louis. Five hundred people gathered at the Jefferson Memorial to hear Young — described as “one of the most eloquent living Confederates” — eulogize the “bravery” and “bitter determination to win” of 600,000 Southern men who fought for a “cause they believed to be right.” The St. Louis memorial (a detail is seen below) was removed in 2017.

*** Prof. Joy M. Giguere, assistant professor of history at Pennsylvania State University, examined Young’s role in raising money for the Jefferson Davis Monument in a recent paper, “Young and Littlefield’s Folly,” published in the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society (Winter 2017).

To download a PDF of this story (without links or images), click here: There was great rejoicing in hell this morning

Nice job, Roland.