A patent medicine mogul who wanted to keep a seat in Congress decided the best way to fight the press was to start his own daily newspaper. It was an expensive mistake.

James Henry McLean, a native of Scotland who arrived in St. Louis in 1849 at the age of 20, amassed a fortune by selling pills, balms, liniments, tonics, and other concoctions of dubious merit.

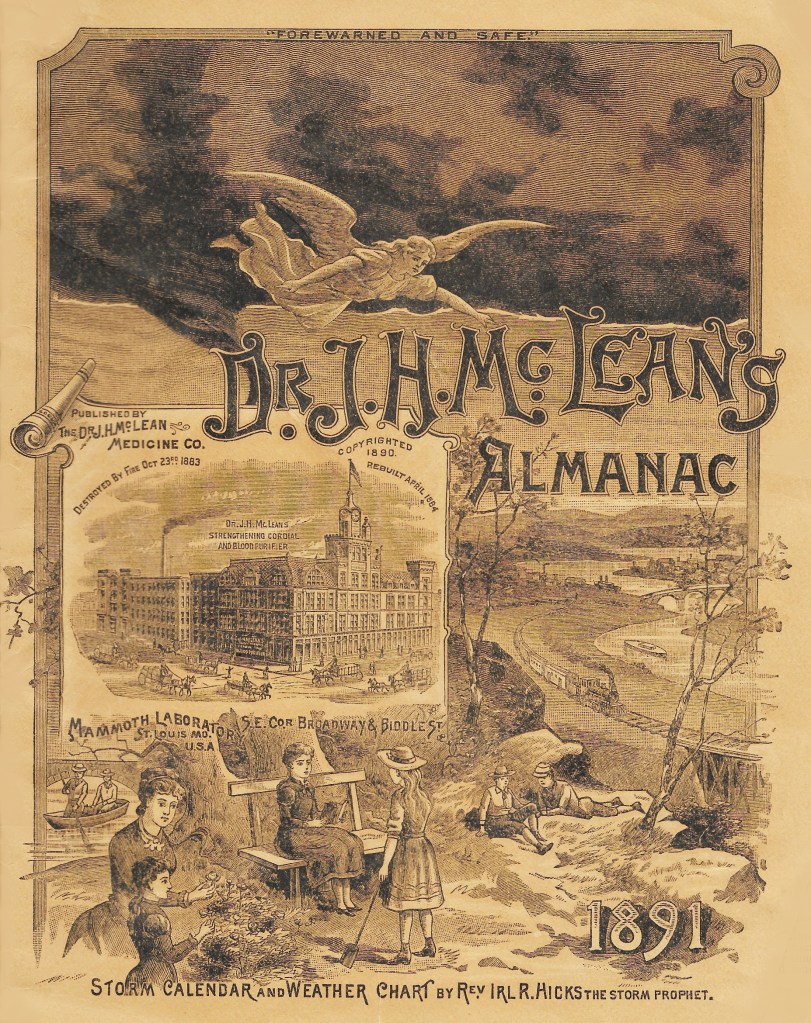

His widely sold products included “Dr. J.H. McLean’s Volcanic Oil Liniment,” “Dr. J.H. McLean’s White Crystal Coated Universal Pills for the Liver,” and “Dr. J.H. McLean’s Homeopathic Liver and Kidney Pillets.” (His “Dr. J.H. McLean’s Strengthening Cordial and Blood Purifier,” advertised as good for treating “puny and weak children or delicate females,” was reputedly 85 to 100 proof alcohol.)

Taxes and tariffs affected his business, but McLean’s interests were not confined just to matters of dollars and cents. He also had an ambitious plan for guaranteeing world peace, outlined in his 1880 book, “Dr. J.H. McLean’s Peace-Makers,” co-authored with inventor and writer Myron Coloney. They called for producing weapons of mass destruction so fearsome that no nation would dare go to war.

In 1882, the sudden death of U.S. Rep. Thomas Allen, a Democrat, offered McLean an opportunity to bring his ideas to a national audience.

He secured the Republican nomination to fill the unexpired portion of Allen’s term in the 47th Congress, as well as the separate nomination for a full term in the 48th Congress.

The Globe-Democrat, the Republican morning newspaper, applauded McLean’s nomination: “The Doctor is a gentleman well known for his business energy and sagacity [and] would make an excellent and useful member of the lower house.”

In an unusual twist, McLean beat the Democratic nominee, James Overton Broadhead, in the contest to fill the unexpired term but lost the same day to Broadhead for the full term. That meant McLean got to serve less than three months, and his time in Congress ended in March 1883.

Five months later, the Globe-Democrat dropped a bomb on the good doctor. McLean’s brother-in-law, Ed Fox, confirmed a “rumor” that local Republican machine boss Chauncey I. Filley had “appropriated” $6,000 of the money contributed by McLean to local GOP campaign organizations — and he had the receipts.

At the time, the Republican Party, which had dominated the U.S. government for a nearly a quarter century, was deeply split — especially on how to rein in the spoils system. In Congress, that fight had played out between U.S. Sens. James Blaine of Maine, a leader of the pro-reform “Half Breed” faction, and Roscoe Conkling of New York, leader of the opposing “Stalwarts.” That division was reflected in St. Louis, where the local press referred to Republicans’ “silk stocking” and “hoodlum” factions. McLean, when he was first nominated, had “silk stocking” support; by paying Filley, McLean hoped to secure “hoodlum” support, Fox told the Globe-Democrat.

The Globe-Democrat, which had no use for Filley, turned on McLean in the run-up to the 1884 election, poking fun at his penchant for “waxing his mustaches in true Napoleonic style, and making impressive pictures as he rides through the principal streets daily upon his coal-black steed.” The story was accompanied by an illustration of a bald, mustachioed McLean astride a giant cannon firing pills and tonics.

Within days of the Globe-Democrat’s gibe, plans for a St. Louis daily newspaper were announced. The new Morning Call, set to debut on the first Monday of June 1884, promised to be “republican,” “earnest and unbiased,” a champion of “the interests of the working classes against oppression in every form,” and “on the side of progress and liberty.”

The announcement did not say who was behind the Morning Call, but it didn’t have to: the newspaper’s address, 314 Chestnut Street, was the same as McLean’s business.

By pricing the paper at 2 cents a copy (the Globe-Democrat was a nickel), the Morning Call hoped to attract working-class readers – a strategy similar to one attempted by E.W. Scripps with the struggling afternoon Chronicle. McLean also assembled a strong, fairly experienced staff – and they quickly built the daily circulation to 5,000. But McLean discovered selling a newspaper was harder than selling liver pills and blood purifier.

As the Jefferson City Tribune reported in early July 1884, “The St. Louis Morning Call seems to be making very poor progress with the work of annihilating the Globe-Democrat. Unless appearances are deceiving the only mission the Morning Call is destined to fulfill is that of depleting the bank account of Dr. J.H. McLean and ‘Boss’ Filley.”

On July 22, 1884 — just 51 days after its launch — the Morning Call was no more. McLean decided to pull the plug after bleeding about $15,000 — nearly $500,000 in today’s money — on the effort.

In a post-mortem, the St. Joseph Weekly Herald said: “The real cause of its death has been attributed to various things, too much Filleyism, too much McLeanism, and too much pills, but the real cause was no money — a very common complaint among newspaper ventures.”

The death of the Morning Call didn’t kill McLean’s political ambitions — nor did it lessen the Globe-Democrat’s antipathy to his candidacy. The paper strongly backed businessman Robert B. Brown, who had built a successful seed oil company, as the GOP nominee in the 9th Congressional District — and Brown headed to the district convention with a majority of delegates.

But that was not enough to overcome the Filley machine. At a raucous meeting that drew police, the boss’ lieutenant, John H. Pohlman, delivered the nomination to McLean thanks, in large part, to bribes paid by McLean.

The Post-Dispatch reported: “A Mr. Kehoe of the Tenth Ward, who had been held up to the Convention as a man who had declined $100 of McLean’s money, offered for the purpose of seducing him, was the object of much denunciation from the Pohlman men, but he maintained that the offer had been made.”

The Globe-Democrat was inconsolable. “If George Washington himself were alive, and attempting to get into Congress by such a gross perversion of honesty and morality, he would not be entitled to the vote of any proper-minded and self-respecting citizen,” the paper said.

The Post-Dispatch piled on, claiming that McLean’s first congressional campaign was fueled by bribes, and even journalists were approached in 1882: “The editor of one of the St. Louis dailies had the insult of a roll of bills tendered to him by this man who aspired to sit where (Thomas Hart) Benton sat.”

Just weeks before the election, the Globe-Democrat suggested McLean — a man it had lauded just two years earlier — might be an undocumented alien. “He has never taken out naturalization papers in St. Louis, and hence, unless he has performed that duty somewhere else, he is still an alien.”

Not surprisingly then, McLean lost the general election by 10 percentage points to the Democratic nominee, John Milton Glover. (That same year, Grover Cleveland became the first Democrat elected to the presidency since the Civil War.)

After the election, the Post-Dispatch said McLean was “indignant, but not crushed,” and was convinced he was the victim of “the most palpable frauds.” McLean told the reporter he had not yet decided whether to contest the results.

McLean, however, was done with politics. And the health of the pill-and-tonic maker was failing. Less than two years after his defeat, while spending the summer near Cape Cod, he died. He was 56.

McLean died a millionaire, but other than his mausoleum at Bellefontaine Cemetery, most what he built in St. Louis — such as the hideous Tower Building at Fourth and Market — has disappeared.

The Dr. J.H. McLean Medicine Company lasted well into the 20th century, and while that company is gone, old advertisements, almanacs and other artifacts are still bought and sold by collectors.

And, remarkably, it’s still possible to buy “Dr. J.H. McLean’s Volcanic Oil Liniment” today. — Roland Klose (Nov. 25, 2025)