Though Fanny Bagby was a trailblazer in her profession, her male peers, predictably, focused more on her appearance than on her achievements.

The first female managing editor of a St. Louis daily newspaper* not only could turn a phrase, she turned heads. And that could prove dangerous.

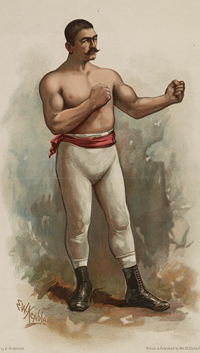

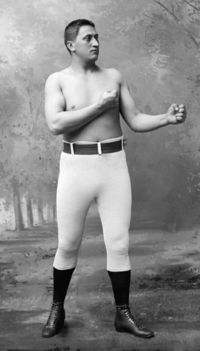

According to a news story by Eugene Field (yes, the “Wynken, Blynken and Nod” poet from St. Louis), Bagby was the only woman present when heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan’s coast-to-coast boxing extravaganza rolled into town in November 1883.

Sullivan had won the heavyweight championship three months earlier at Madison Square Garden by beating Herbert Slade, a New Zealander known as the “Maori” (his mother was a member of the Ngāpuhi Nation).

Slade joined Sullivan’s tour – and their fight appears to have been the main event on the card in St. Louis. But Bagby, who was there with other members of the St. Louis Evening Chronicle staff, was the main attraction, at least for one of the pugilists.

Here’s part of Field’s account for the Chicago Daily News:

“Miss Bagby’s trim figure, bright black eyes, and handsome face attracted the attention of Herbert Slade, the athletic Maori, and it was while casually glancing at her during his bout with Sullivan that he received that terrible blow in the mouth that knocked out two of his teeth, and sent him reeling.”

After the match, Slade asked to meet Bagby, where “the charming young editress felt of his muscle and his knuckles, and fired more questions at him in ten minutes than he could have answered in six months.” Slade sought permission to correspond with her, which she granted.

Field, waxing away about Bagby’s many wonderful qualities, declared she was “bright as a dollar, as earnest as a weasel, as good as gold, and as pretty as a picture. She is violently in love with her profession, and has steadily risen in it from the start.” (Field appears to have broken new ground by turning a weasel comparison into a compliment.)

In a later story, Field gushed how the “beautiful young editor” of the St. Louis Chronicle had with her fair cheeks, timid blushes and fawn-like eyes the power to disarm any aggrieved “mad man…, frothing at the mouth and thirsting for a human life.”

Field continued: “Yet in reality she is no coward. Emergencies have arisen in which this fair young journalist has demonstrated her pluck and agility. It is to her credit that she never goes armed, and she will not even adopt the precaution of keeping a pistol in the drawer of her desk. But she can slap and scratch with marvelous dexterity, and huge, hulking men have been seen tottering out of her presence with their eyeballs hanging out on their cheeks, and their noses split open like a quail on toast.”

‘BROTHERLY AFFECTION’

Frances Mary Bagby was born in 1851 in Rushville, Illinois, the oldest of nine children. Her father, John Courts Bagby, was a successful lawyer in Schuyler County who served a term in Congress and was later appointed a circuit court judge. Her mother, Mary Scripps Bagby, was part of the newspapering Scripps family and, as noted above, the mother of nine children.

Fanny Bagby’s first newspaper job was at her second cousin James E. Scripps’ Detroit Evening News; she moved to St. Louis to join the Chronicle in 1880 where Edward Willis Scripps, another second cousin, was initially calling the shots. James and E.W. were half-brothers.

E.W. Scripps, with help from his siblings, started and acquired more than two dozen newspapers, creating the nation’s first newspaper chain. While Scripps was alive, his papers sought a working-class readership, and his papers were priced accordingly. In St. Louis, while the Post-Dispatch was charging a nickel per copy, the Chronicle sold for a penny.**

Bagby didn’t stay long in St. Louis. In 1884, she left for Minnesota at the invitation of editor Stanley Waterloo, who had started The Day in St. Paul. The married Waterloo had worked with Bagby at the Chronicle, and they had high opinions of each other – too high, perhaps.

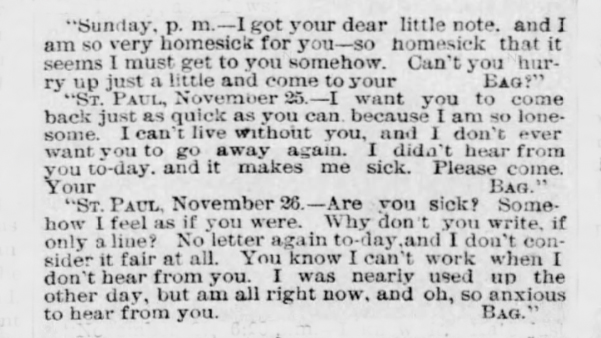

In 1884, while Waterloo was in St. Louis and Bagby in St. Louis, a disgruntled employee of The Day, entrusted with handling their correspondence and worried he was going to lose his job, had photographic copies made. Here’s a snippet of what Bagby wrote Waterloo: “I am so lonesome. I can’t live without you, and I don’t want you to go away again.” Here’s another: “I want to see you so much – more every minute…. I love you, and I want you to succeed; but you will anyhow. I’d love you anyway.”

Waterloo and Bagby, when they learned their letters had been copied, provided them to the competing St. Paul Pioneer Press, hoping to tamp down any suggestion that their relationship was illicit, insisting instead they were like “brother and sister.” Their decision to come clean, of course, backfired – and other newspapers eagerly shared their private correspondence. (The St. Louis Post-Dispatch headlined its story “Stanley’s Waterloo.”) When The Day went belly-up soon after, one account snarked: “It was killed by a combination of circumstances (including) too much brotherly affection for Miss Bagby.”

Waterloo went to work for the Chicago Tribune, then became a novelist. He later accused Jack London of plagiarizing his best-known work, “The Story of Ab.” (London conceded he had leaned on Waterloo for inspiration for his “Before Adam,” but wrote a better version of the tale.)

After St. Paul, Bagby headed to San Diego “to recover her health,” and ended up working for the Union. She was city editor of the Union in 1891 when she married the newspaper’s editor, Paul Blades. She invited E.W. Scripps to visit, and the newspaper magnate fell in love with the city and region, and built Miramar, his palatial estate.

The newly married Fanny then convinced Scripps to finance the purchase of the San Diego Sun for Blades and a partner. Scripps. also helped her youngest brother, Edwin Hanson Bagby, get established in the newspaper businesses. Scripps later expressed regret for helping both men – and memorialized that regret in a 9-page “disquisition” in 1910. A copy of “To Help is to Hurt” is archived by Ohio Universities Libraries at this website: https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/scripps/id/3994/

Fanny Bagby did not live to read Scripps’ rebuke of her husband and her brother. In 1908, she returned to Rushville when she learned her mother was at death’s door. Fanny, who had been in poor health, collapsed at her family home, and died a few hours later. She was 56. — Roland Klose, Oct. 23, 2025

* I couldn’t find any earlier ones.

** Gilson Gardner, in “Lusty Scripps” (his 1932 biography of E.W. Scripps) explained why Scripps’ strategy ultimately failed in St. Louis: “In other fields, E.W. had been fortunate in having conservative opposition. (Joseph) Pulitzer was just as good a friend of the workingman as was E.W. and he was in some respects a more brilliant and better equipped editor.”

- Postscript: In 1905, the Scripps-McRae chain, the money-losing Chronicle’s owner, acquires Nathan Frank’s St. Louis Star. The paper is renamed the Star-Chronicle. Frank retains a minority share in the publication.

- In 1908, Scripps gives up on St. Louis, and the Star-Chronicle is sold to Edward G. Lewis, the magazine publisher who built what’s today’s City Hall in University City. The paper is renamed the Star.

- In 1912, Frank reacquires the daily after Lewis got into trouble with the feds for fraud and sought bankruptcy protection.

- In 1913, businessman John C. Roberts, an executive with International Shoe Co. and proponent of “clean government,” buys the Star.

- In 1932, Elzey Roberts, son of John Roberts, is publisher of the Star when the paper takes over the competing afternoon St. Louis Times. The paper is renamed the Star-Times.

- In 1951, the Post-Dispatch acquires the Star-Times and closes it.