St. Louis reporters used to fight to get the news — each other, that is. One of the most spectacular examples of fisticuffery came in 1883, when scribes for the city’s two English-language morning papers came to blows at the old Four Courts building.

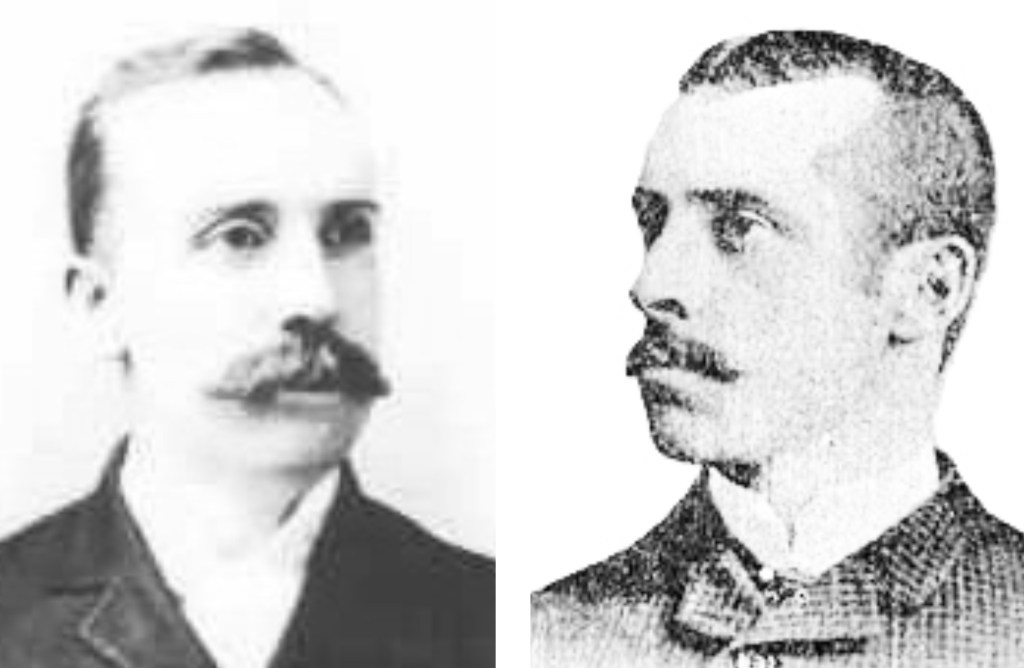

John Fay, 22, of the Missouri Republican and John C. Klein, 26, of the Globe-Democrat were recent Chicago transplants, which may have explained their aggressiveness.

Klein, who arrived in St. Louis after Fay, was convinced Fay was working to sabotage him by asking the police chief and other officials not to give him any news. On Oct. 30, Klein confronted Fay at the Four Courts, demanding an explanation. As a Post-Dispatch reporter recounted: “A spirited conversation ensued, culminating in a fight.”

Fay hit Klein, Klein hit back, and a dozen or so blows were exchanged. Fay managed to get Klein’s pinky finger in his mouth “and held on to it with a bulldog tenacity,” the Post-Dispatch reporter recounted. Police had trouble separating the two men, because Fay was “deeply engaged in masticating Klein’s finger and holding onto it like a vise.” Both men were arrested and charged with disturbing the peace, but were released on their personal recognizance. Prosecutors dropped the charges on Halloween.

The Post-Dispatch reporter — the article didn’t have a byline — said he later “reconciled” Fay and Klein, adding “at some cost to himself and some profit to the proprietor of a saloon across the street.”

The Post-Dispatch scribe, however, unhelpfully added that Klein is a “favorite at the Four Courts, and the sympathy felt for him is in proportion to the contempt felt for Fay.” Klein, the Post-Dispatch predicted incorrectly, was likely to lose his little finger because of the “ragged, dangerous wound.”

The Post-Dispatch headlined its story “The Chicago Style”; the New York Times’ headline on its next-day story, which leaned heavily on the Post-Dispatch’s account, was “Ruffians of the Western Press.”

The Fay-Klein dustup, however, wasn’t the end of the story.

Two days later, Fay ambushed Post-Dispatch reporter Michael Angelo Fanning, 26, outside a courtroom. Fanning apparently was responsible for the story about the Fay-Klein fight, and Fay didn’t like it one bit.

Fanning was taken by surprise by the attack, but after taking a few blows, he knocked Fay down. The two tussled some more before being separated, and the Post-Dispatch added the “assault was made without a word of warning and in a most unmanly and cowardly manner, and with the ferocity of a wildcat.”

It appears the Post-Dispatch was the only local paper to cover the fights, so there is no record of Fay’s version of events. It didn’t seem to damage anybody’s career, though.

For all three reporters, St. Louis was an important stop on the way to fame and fortune:

JOHN FAHEY

Fay, whose actual surname was Fahey, built a reputation in St. Louis that continued long after his departure. W.A. Kelsoe, in his 1927 retrospective on the rough-and-tumble era of local newspapering, “St. Louis Reference Record,” said Fay was “one of the best Four-Courts reporters ever assigned to that building.”

After making his mark on St. Louis (and on Klein’s finger), Fay spent about 30 years as the Chicago correspondent for the Pulitzer’s New York World, beginning in 1890. Among his big stories: the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. His byline appeared on the front page of both the World and its St. Louis sister paper, which described him as the “Chicago correspondent of the Post-Dispatch.”

Fay, or Fahey, died in 1947. He was 86.

JOHN COXON KLEIN

Klein achieved national fame and notoriety in 1888, while covering the first Samoan Civil War. There our intrepid correspondent gained the confidence of Mata’afa Iosefo, a chief who had been deposed by German colonists seeking control of the islands. Klein’s warnings about an imminent invasion allowed Iosefo’s warriors to repel an attack on Dec. 18, resulting in 57 German casualties, including 23 deaths.

Facing arrest by the Germans, Klein sought refuge on an American warship. The Germans demanded the Americans surrender Klein, then threatened to open fire after the U.S. warship refused. The timely intervention of a hurricane, which destroyed the entire German fleet and two American cruisers in Samoa, helped avert a war between the two nations. Klein made it back stateside, where he said he’d been merely a passive spectator during the battle, too sick to take part.

Klein’s eclectic career took him many places. He was present at the Cook County Jail in 1887 as doctors sought to save anarchist Louis Lingg who blew off half his face with a blasting cap in an attempt to cheat the hangman. In 1890, Klein wrote about the abuse of prisoners in Georgia for the New York World. He attempted the launch of a weekly newspaper in San Francisco in 1890, called the Cynic. It lasted four weeks. He later covered the Boer War for the New York Herald.

Klein died in 1938, aged 81.

MICHAEL ANGELO FANNING

Fanning, the other St. Louis reporter allegedly attacked by Fay, had a newspaper career punctuated by politics. Before the Post-Dispatch, he had worked at the Republican. In 1885, he was working as city editor of the Globe-Democrat, married “one of the most popular society ladies of the city,” then briefly rejoined the Post-Dispatch.

In 1886, he went to work for David R. Francis, mayor of St. Louis and later the governor of Missouri. In 1891, after Fanning was done with Francis, he returned to his “first love,” and co-founded The Sunday Mirror in St. Louis. (That paper later achieved fame as Reedy’s Mirror, edited by William Marion Reedy.)

In 1899, Fanning returned to his native city, becoming secretary of the Cleveland Municipal Association. There, he aligned with Democrat Tom L. Johnson, the future reform mayor of that city. Fanning never broke completely with newspapering: His last job was research editor for the New York Evening Post.

Fanning died in 1937 at the Los Angeles home of his daughter. He was 80. — Roland Klose, Oct. 20, 2025