Political passions ran deep in the frontier town of St. Louis in the early 19th century, where disagreements about national issues regularly turned violent. Newspapers, which served as voices of political factions, helped provoke the violence — and often suffered the consequences.

Among the instigators was The Missouri Argus, whose owner was savagely beaten by the target of a vituperative editorial attack.

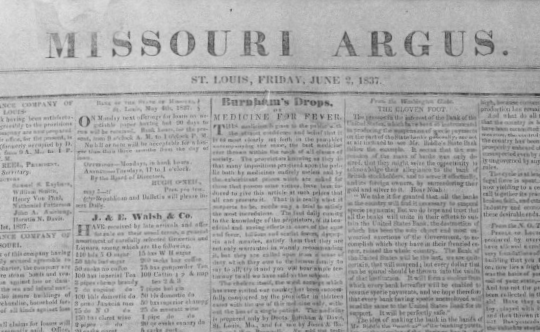

Founded in 1835, the Argus was the voice of the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson and Thomas Hart Benton, then in control in Missouri but facing a challenge from the ascendent Whigs, a new party aligned with wealthy landowners and business interests.

On Nov. 19, 1839, the Argus was acquired by Andrew Jackson Davis, a young lawyer who moved to St. Louis from Massachusetts in 1836, when he was 21.

Contemporary accounts described Davis as well-liked, whose “manners were mild, bland and courteous” and who “never spoke evil of any one.” That was a marked contrast to the Argus’ editor, William Gilpin, whose fulminations were anything but mild, bland or courteous, especially in the run-up to the 1840 presidential election.

On May 30, 1840, Gilpin aimed a shot at proponents of a national bank — long a bugaboo of Jacksonian Democrats —that included this broadside: “Nothing that has yet occurred in the present contest more clearly proves the dunghill breed of the Federalists than this movement, and the toadies made use of it to play off the game.”

William P. Darnes, a St. Louis ward politician and carpenter by trade, took offense, and immediately addressed a letter to Davis, written and delivered by Col. Thornton Grimsley, a leading St. Louis Whig, demanding an explanation.

Darnes said he was addressing Davis and not Gilpin because “I consider you the only person to be held responsible for what appears in that paper. As the editor’s standing, in my opinion, for moral integrity and veracity forbids that I should have any communication with him, therefore, sir, I wish you to inform me by the bearer, Capt. Grimsley, if the following language was intended to be applied to me, directly or indirectly, in any shape, manner or form.” He then repeats the “dunghill breed” quotation.

Davis immediately responded, writing: “To Thornton Grimsley, Esq.: Sir — From the character of the author, and of the contents of the letter which you handed me this afternoon, it is entitled to no notice or reply from me. I therefore inclose it to you, to be disposed of as you may think proper. Yours respectfully.”

Two days later, Gilpin unloads on Darnes in the Argus:

“A fellow by the name of w.p. darnes, a common street-loafer and vagabond, and fit subject for the ‘vagrant act,’ had the impudence, on Saturday last, to send a note by Thornton Grimsley to the proprietor of the Argus, Andrew J. Davis, asking from him the meaning of certain phrases of ours which appeared in the paper of that morning. The blackguard style in which the note was couched, the degraded character of the fellow who had put his name to it as the author, rendered it necessary, of course, that it should be returned to Mr. Grimsley without a reply.

“None but a jackass or poltroon would think of calling explanations of the meaning of an article, deemed offensive, except by making application to its known and acknowledged author.

“Mr. Davis is, of course, no more competent to give the meaning of our article than any other equally intelligent individual. This half-witted drone, who stands at the corners or roams about the streets without employment, and without seeking it, and without any visible means of support, is a fit today for the little clique of Federalists, with Chambers at their head to hiss on the sending of threatening letters, which they themselves dare not venture to underwrite. The editor of this paper is William Gilpin, as is apparent from its face, and HE HOLDS HIMSELF RESPONSIBLE for all that appears in the Argus as editorial….”

That very day, Darnes bought an iron cane with a lead head of about three-quarters of an inch diameter, then made his way to the National Hotel at the corner of Market and Third streets (near the present-day location of the Gateway Arch). Davis was staying at the hotel; Darnes planned to intercept him as Davis returned for dinner. The two men met outside the hotel. Witnesses saw them converse, then watched as Darnes struck Davis repeatedly. Davis, a much-smaller man armed with only an umbrella, quickly fell to the ground, with multiple fractures to his skull and bleeding profusely. He was taken to the hotel, where surgeons struggled to mitigate the extensive damage, pulling shards of bone out of his brain and using a trephine — a hole saw — to remove some of the damaged skull. Davis, after a week in agony, died on June 8, 1840.

The Globe-Democrat, which revisited the case in 1879, said the facts would have warranted a charge of murder in the second degree, but facts weren’t the only things that mattered in a high-profile trial that drew wide interest across the city, including the unusual spectacle of “ladies” sitting through the trial.

After hearing the testimony, a jury found Darnes guilty on Nov. 14, 1840, of manslaughter in the fourth degree — “the involuntary killing of another by a weapon, or by means neither cruel nor unusual, in the heat of passion, in any case other than justifiable homicide.” Darnes was fined $500 — “tantamount to an acquittal” and “certainly as great a legal farce as was ever enacted in a Court of law,” the Globe-Democrat wrote.

The Globe-Democrat attributed the sentence, in part, to the ignorance of jurors (“a good portion of almost every panel is composed of men who know about as much of the English language as they do of the Choctaw tongue or Comanche dialect”) and to “political considerations” (“Such of the jury as belonged to the Whig party were readily induced to believe that a verdict against Darnes implied a censure of the whole party, while the Democratic portion sought to inflict upon him the highest punishment known to the law, and this brought about a compromise verdict.”)

After Davis’ death, Argus founder Abel Rathbone Corbin reacquired the paper (“at the request of the Democratic Party”) but sold it the following year, and it was renamed the Missouri Reporter. In 1846, the Reporter changed hands and was combined with another newspaper to create the St. Louis Union. The Union then was folded into the Democrat and later combined with the Globe, becoming the Globe-Democrat, a daily newspaper that lasted until 1986.

Gilpin, who left the Argus in 1841, had an eclectic career as an explorer, politician, land speculator, and soldier. In 1861, he secured President Abraham Lincoln’s appointment as the first governor of the Colorado Territory, but his mismanagement ended his tenure after a year. Later, he became a land speculator in New Mexico. He died in 1894, at the age of 80.

As for William Darnes, he moved to Commerce in Scott County, where he became a farmer and was elected repeatedly to the Missouri House of Representatives. He became “prominent in that body,” an obituary in the Ste. Genevieve Plaindealer said, “for his sound judgement and quick perception.” But he remained a brawler. In 1858, when the local justice of the peace refused Darnes’ demand for an arrest warrant, Darnes attempted to strike him with a four-pound weight. In the tussle, Darnes was shot. Though his injury appeared grave, he survived. He died in January 1861, at the age of 50. His wife and two children predeceased him.

It’s unclear (at this writing) where, if anywhere, Davis is buried. His broken skull was displayed during Darnes’ trial, which took place five months after the death. In November 1840, a bill was introduced in the Legislature to name one of 15 new Missouri counties “Andrew J. Davis, in testimony of the private worth of Andrew J. Davis, late Proprietor of the Missouri Argus, who was savagely murdered in St. Louis.” Andrew County is in the northwestern corner of the state, a region Davis never saw.

(Originally published Jan. 20, 2025)