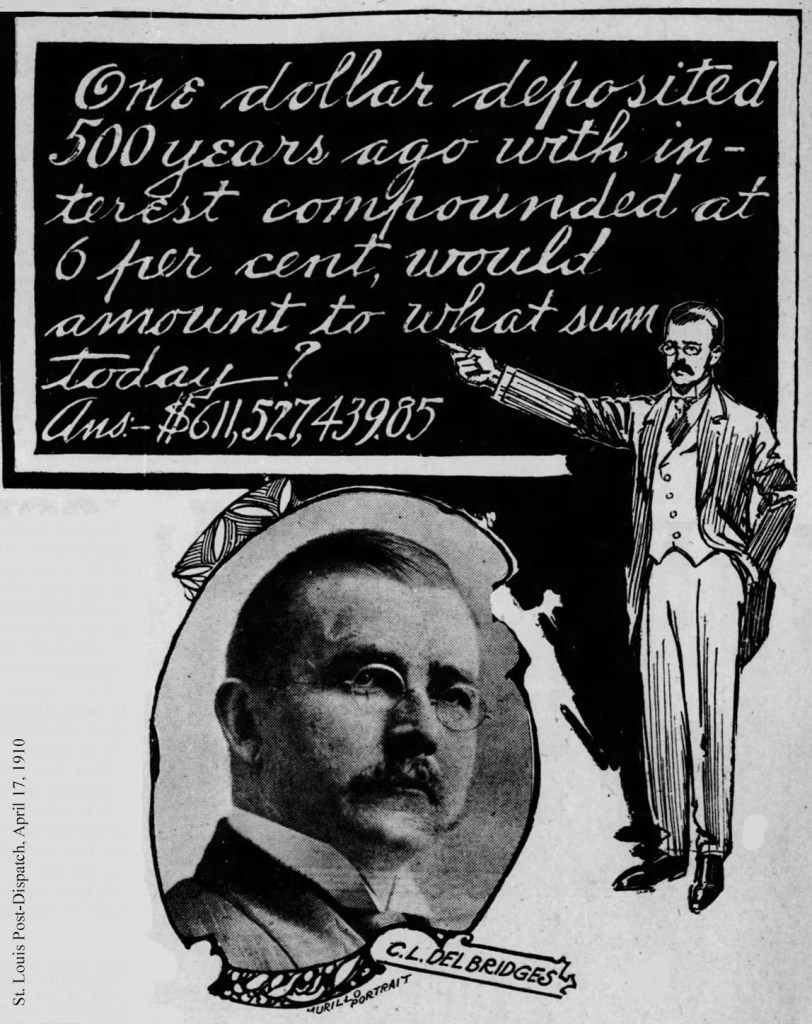

As a schoolboy, Charles Lomax Delbridge discovered a remarkable faculty he didn’t quite understand — an ability to quickly solve multiplication problems involving fractions. He later described the process to a reporter: “It seemed to me that I simply telegraphed the problem into my brain and that scarcely an instant elapsed until the answer came flashing back.”

In 1878, when he was 13 and still living in the South, he decided to produce a book of calculations for the cotton trade that showed the aggregate value of any commodity based on weight and price. That three-year effort led to other “mathematical” books, including interest rate tables widely used by banks.

Twenty years later, Delbridge relocated to St. Louis, then one of the nation’s leading industrial and commercial hubs, and built a publishing business.

His success afforded him time to dabble in other matters, including civic improvement.

Reforming things was not an uncommon avocation for St. Louis businessmen as the nation moved from the Gilded Age into the Progressive Era; as employers, they were acutely aware of the social and political pressures caused by terrible housing and working conditions. Wealthy manufacturer Nelson O. Nelson, a self-described socialist, was among those reformers. He is credited with establishing the cooperative community of Leclaire — now part of Edwardsville, Illinois —in 1890.

Like Nelson, Delbridge also attempted to launch a sort of cooperative community. It was a chance to test his belief that it was possible to have a town with no police, courts, taxes or even politics.

In 1925, he acquired about 1,600 acres in the southwest corner of Washington County, Missouri. His plan was to build a grocery and other buildings, then rent to people who agreed to live by the “Golden Rule.” The town would bear his name.

His experiment got more publicity than traction. Newspapers around the country wrote about “another utopia,” but many questioned how a town owned entirely by its founder and occupied by renters could last. How would the town of Delbridge, lacking courts and police, be able to rid itself of scofflaws?

Charles Delbridge never moved to his eponymous town, but left his brother, Robert, in charge. When Delbridge, the founder, died in 1934, Delbridge, the town, had a population of about 50.

Unincorporated Delbridge still shows up on maps — it’s about nine miles west of Belgrade on Route C, or 85 miles southwest of St. Louis — but most of the structures dating from that era were gone by 1972, the last time the St. Louis Post-Dispatch visited.

Delbridge’s first big crusade wasn’t aimed at improving humanity, but rather just fixing the city’s awful streetcar system. Like many in St. Louis, he was furious that the United Railways, the streetcar monopoly, refused to run enough cars. That meant passengers were jammed like sardines, if they could get onboard. In 1914, he complained to the Missouri Public Service Commission that the “tremendous pressure” caused by the overcrowding forced a two-pound beefsteak out of his overcoat pocket. (He got back on the car and retrieved the steak, which was wedged between the shoulders of two straphangers standing back-to-back.) Delbridge became a leading advocate of public ownership of the transit system.

Delbridge also styled himself a sort of criminologist, having produced in 1916 a pamphlet titled “The tragedy, the farce and the humbug of the courts.” In it, he made a case that crime was promoted by the criminal justice system which profited from its existence.

That was a view he held for years, and one he carried to his grave. In 1912, during a rate hearing in front of the Interstate Commerce Commission, Delbridge was admonished for calling the courts “the refuge of thieves and murderers.”

In 1927, he wrote the Post-Dispatch: “In the course of auditing work, I have had occasion to check the records of many cases, civil and criminal, that have been through the courts, and so far as I have ever been able to figure it out … there is not on this earth today and never has been a town, city, county, state or nation, where courts were operated for any purpose whatever, other than as a cost mill for the benefit of courthouse hangers-on, lawyers and the various kinds of taxeaters.

“In other words, it is the gunmen, the murderers, robbers, burglars and thieves who provide the pretexts for the taxeaters to levy and collect heavy taxes, ‘costs’ and ‘fees’ under the pretext of it being necessary in order to suppress crime.”

Delbridge’s orientation, one that saw exact relationships between variables, also led to other simplistic solutions to complex problems.

For example, while Europe was in the throes of the Great War, Delbridge offered a 5-cent pamphlet that outlined his plan to achieve lasting peace: offer any enemy soldier $1,000 to desert. “I know human nature,” he said. “There is not an army or a navy on earth today that could be held together in the face of such a reward.”

Another nonstarter: Delbridge hit upon an answer to Missouri’s hot summers by urging Union Electric Co. in 1931 to freeze its central Missouri lake, the Lake of the Ozarks, “from top to bottom and from one end to the other.” Some of the ice would remain through the summer months, he said, turning that part of Missouri into a “regular arctic health and summer resort.”

Delbridge left an estate of about $20,000 — about $475,000 today — and was buried in Valhalla Cemetery. His son, Charles Jr., ran the business until his death in 1953. (May 25, 2025)