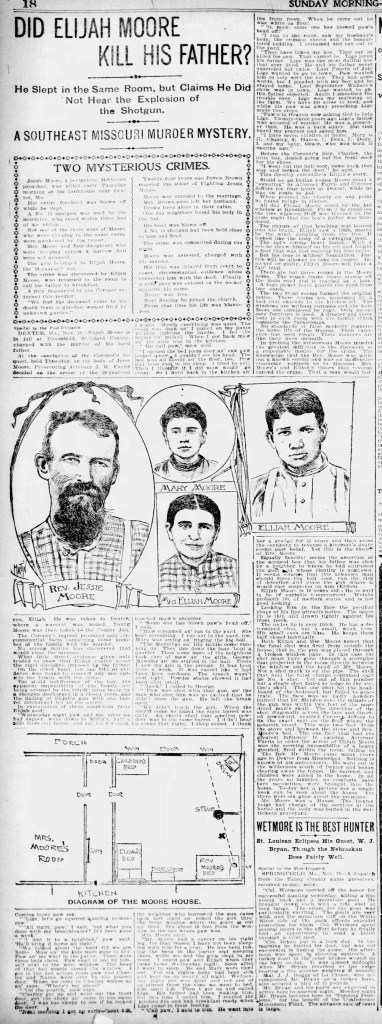

The Rev. Jesse Moore’s forehead was blown off with a double-barreled shotgun on Nov. 16, 1899, and suspicion immediately fell on his 19-year-old son, Elijah “Lige” Moore, who was sleeping in the same room that night, but claimed not to have heard the shot.

A lengthy account of the murder, published three days later by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, was not sympathetic to Elijah. Among many observations, the newspaper asserted the boy was stolidly indifferent to his father’s death and “not good looking.” It could only speculate about a possible motive but clearly did not put much stock in what Elijah and his mother, Margaret, were saying.

“The knowledge that the Rev. Moore was without a known enemy and was an inoffensive character compels us to discount Mrs. Moore’s and Elijah’s theory that revenge caused the crime,” the Post-Dispatch wrote.

Jesse Moore, a “peripatetic Methodist preacher,” was undeniably strict, and the family’s circumstances — poor farmers in the Bootheel town of Dexter — were difficult. (A reporter noted there wasn’t a picture or a single book in their home, but they did have six guns.)

Still, Elijah’s mother insisted her boy was incapable of the murder.

“They say he killed his paw. That cannot be. Lige loved his father,” she told the Post-Dispatch reporter. “Lige was the most dutiful boy that ever lived.”

But two days after murder, Elijah confessed to Joseph W. Farris, the Stoddard County prosecuting attorney.

Farris, in his version of how he obtained the confession, said he told Elijah, “People in your country believe that you know something about who killed your father, and … I believe it too.” After repeated denials, Elijah then said his 15-year-old sister, Mary, did the shooting. But Farris said he doubted a young girl who never fired a gun before would do the killing — she’d be too afraid.

Eventually Elijah relented and gave a full confession.

“My pa never did treat me right,” he said, according to Farris. “I worked awful hard all my life on the farm there.” Elijah complained that his father wouldn’t buy him clothes — other than a cheap suit — and wouldn’t let him stay out late with girls, go to shows or parties, even though he was “getting near grown.”

On March 15, 1900, a jury found Elijah guilty of the murder — largely because of the confession — and a judge sentenced him to hang in Bloomfield, the county seat, on May 18.

His lawyers’ arguments to the trial court that the confession had been coerced formed the basis of his appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court: Farris effectively scared a confession out of him by referring to the propensity of many Missourians to lynch people before justice had run its course.

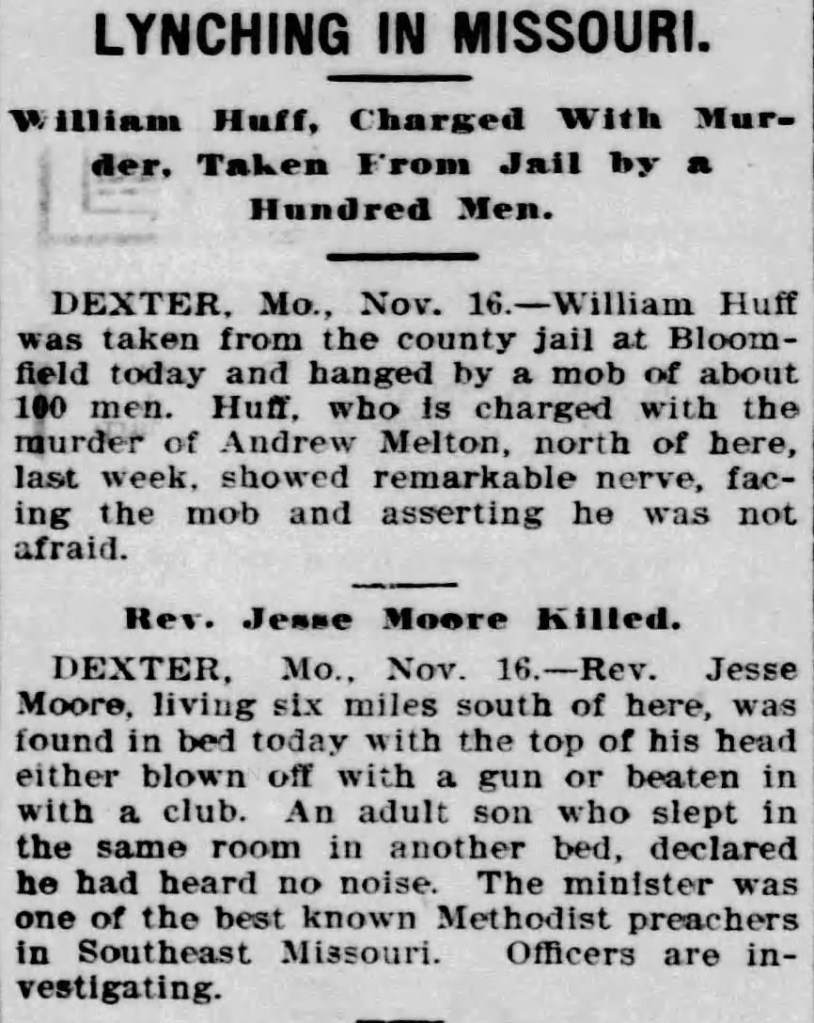

In fact, on the very day that Jesse Moore was murdered, a mob lynched a prisoner named William Huff — and the tree where Huff died was visible from Elijah’s cell.

Elijah later testified that Farris told him: “There is a mob on the streets and one in your county, and, by God! I can’t save you unless you do what I say.” Moreover, Farris warned Elijah that his mother and sister would face the same fate: “Tonight you and your mother and your sister will be hung if you don’t acknowledge to this, but if you do I will save you all.” That conversation was overheard and corroborated by the jailer’s spouse, who was present.

Based on this testimony, the Missouri Supreme Court on Feb. 26, 1901, reversed the lower court, ruling “a confession procured by express or implied representations that it is the only way to protect accused from mob violence is not admissible.”

A second trial was held, and Elijah was acquitted in June 1901. (Not everyone was convinced of his innocence. The Democrat published in nearby Caruthersville groused: “Elijah Moore, who was convicted of killing his father, Rev. Jesse Moore, … was acquitted last week. The parson is in glory, no doubt, and if Elijah ever tries to break in what the old man will do for him will be a plenty.”)

Jesse Moore’s killer is unknown. In December 1899, a man named Adkins said he and a companion had committed the murder — and, learning of Adkins’ confession, Elijah retracted his. But there’s no record of anybody else being charged with the crime.

Elijah L. Moore died of natural causes in 1947. He was 66.

His obituary in the Dexter Statesman said Elijah was “always interested in civic affairs and stood firm for what he believed to be right.” It made no mention of the 1899 murder.

In addition to his two terms as Stoddard County prosecutor, Farris served as president of the Bloomfield board of education, mayor of Bloomfield and two terms in the Missouri Senate. He died in 1941 at the age of 74. — Roland Klose (Nov. 16, 2024)