John W. Jacks was in his time an esteemed newspaperman, a native Missourian who started, owned and edited several publications before buying the Montgomery Standard in 1881 and editing the weekly for some 40 years. He was politically active, accepted state and federal appointments, ran for office and used his position and his paper to advance his interests. “One of the ablest newspapermen in Missouri” is how he was described in news stories about his death published across the state.

None of those reports, however, cited Jacks’ most notorious contribution to Missouri journalism, when, as president of the Missouri Press Association, he responded to British anti-lynching activist Florence Balgarnie’s solicitation of support by sending a racist broadside.

Dated March 19, 1895, Jacks’ letter to Balgarnie accused African Americans of being “wholly devoid of morality” and asserted Black women “are prostitutes and … natural liars and thieves,” while insisting “our laws mete the same punishment to both white and colored people for the same crimes … and no discrimination on account of color.”

“Your plea,” Jacks wrote Balgarnie, “seems to us to take the form of asking us to make associates for our families of prostitutes, liars, thieves and law-breakers generally, and to especially condone the crime of rape if committed by a negro. Respectable people in this country not only decline to form such associates, but naturally infer that those who ask them to do so and place themselves on a level with such characters must either be of the same moral status themselves, or else wholly ignorant of the condition of affairs here, and consequently do not know what they are talking about.”

A reprinted copy of the full Jacks letter is included in the Mary Church Terrell papers at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center of Howard University.

Balgarnie forwarded the Jacks letter to Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, a leading suffragette and founder of The Woman’s Era, the first newspaper published by and for Black women. Ruffin included a copy of the letter in her call for the first National Conference of Colored Women, which was held July 29-31, 1895, in Boston:

“The letter of Mr. Jacks which is also enclosed is only used to show how pressing is the need of our banding together if only for our protection…. We do not think it wise to give this letter general publishing and ask you to use it carefully.”

While the Boston conference, which birthed the National Federation of Afro-American Women, dealt with a range of issues, Jacks was never out of mind. He was denounced in a resolution “as a traducer of female character, a man wholly without sense of chivalry and honor, and bound by the iron hand of prejudice, sectionalism, and race hatred, entirely unreliable and unworthy the prominence he seeks.” And his name was invoked repeatedly by representatives of organizations who gathered at the conference. (From St. Louis, a letter to the conference, signed by the Rev. W. J. Brown and Lavinia Carter, decried the “foul slander upon our people” that emanated from Missouri, and “emphatically protest against the truthfulness of the same.”)

Very little about Jacks’ letter and the ensuing controversy appeared in Missouri newspapers at the time* and that has fueled some misinformed speculation that the letter itself was a fabrication, perhaps by Balgarnie or others to steel the resolve of those in the anti-lynching movement.

The Christian Educator, a publication of the Methodist Episcopal Church’s Freedman’s Aid and Southern Education Society, made an effort to learn more about Jacks, and sent letters of inquiry to “prominent people of Missouri.” A summary of the Educator’s report, which mentioned no names, was published in the January 1896 edition of The Woman’s Era, and suggested Jacks’ letter to Balgarnie was inconsistent with what was known about his character. According to one reply, “There are several of the leading colored men of this town and county that are subscribers to Mr. —-’s paper, and he has never printed a disrespectful word in his paper here against the colored people.” While some digital editions of the Educator from that time period are available, a copy of the original report could not be located.

Still, given the preponderance of evidence, there’s little doubt Jacks authored the letter, even if it didn’t cause much of a ripple back home. Jacks’ status and the fact the white-owned press, especially in the 1890s, was run by people who likely shared his views, the lack of coverage by other newspapers, including those in Missouri who knew Jacks, shouldn’t be a surprise. Even the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, at the time under control of Col. Charles H. Jones, a Confederate veteran, was riddled with racist news coverage, illustrations and advertisements.

Jacks’ letter also reflected the widespread sentiment in the South and in border states that anti-lynching activists, especially on the other side of the Atlantic, were gullible victims of fabrications and propaganda. In fact, the sitting governor of Missouri, William Joel Stone, denounced Ida B. Wells-Barnett as she made her first tour of England to promote the anti-lynching cause. In a letter published in a London daily in 1894, Stone insisted “the negroes are, in every respect, as well treated in Missouri as in Massachusetts or in any other state,” and called Wells-Barnett’s accounts of lynching “absurd.” And yet, lynching continued in Missouri and other states well into the 20th century.

Jacks’ letter also is consistent with his own history. Born in Monroe County in Missouri’s Little Dixie region, he was the son of a native Kentuckian whose Confederate sympathies forced the family to move briefly out of the state during the Civil War. In 1878-79, before he bought the Montgomery City newspaper, Jacks was part-owner of a St. Louis book publisher whose titles included John Newman Edwards’ “Noted Guerrillas,” a sympathetic portrait of murderous brigands like William Quantrill, “Bloody Bill” Anderson, and the James brothers. (Edwards also was a newspaperman, best known as the founder of the staunchly Democratic Kansas City Times.)

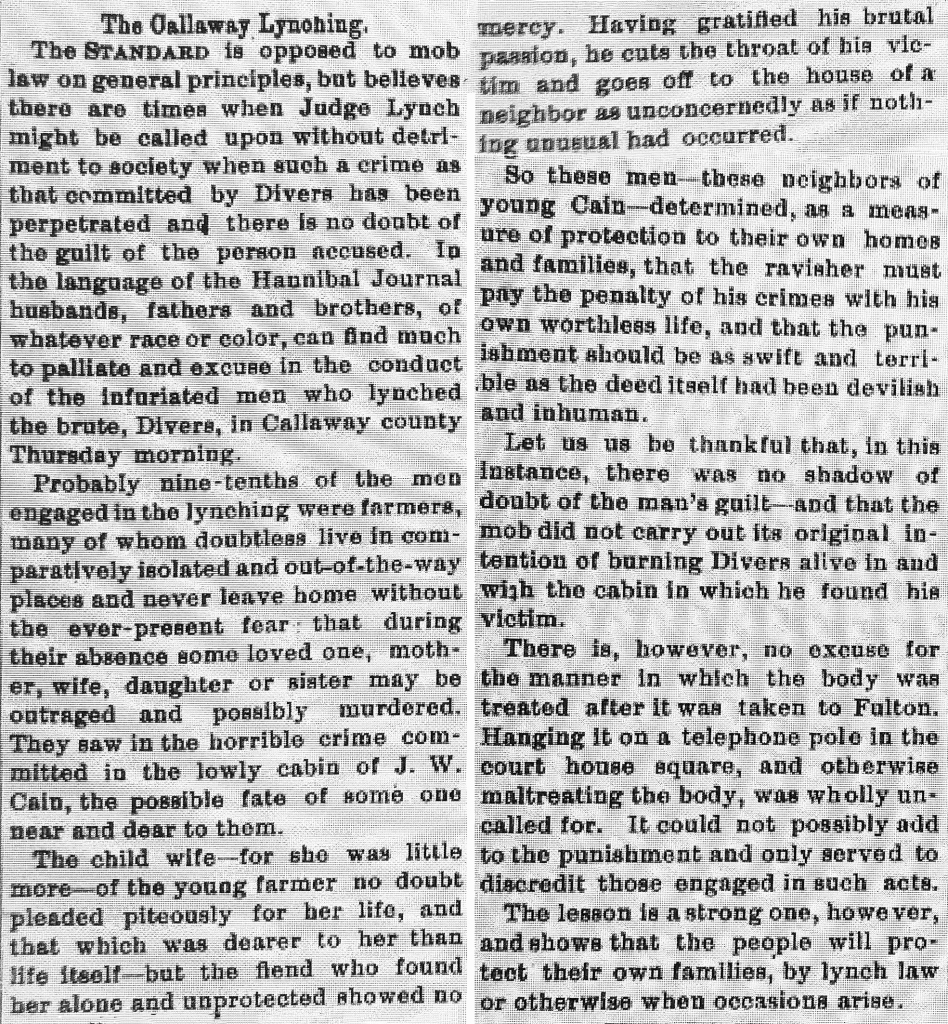

The Montgomery Standard, based on a review of editions from March through August 1895, did not publish anything about Jacks’ letter or the heated response. The weekly’s content during that period — commercial notices, summaries of lawsuits, legislative reports, reprinted stories from other newspapers — did not appear to reflect any of the explicit bigotry that Jacks expressed in his letter to Balgarnie — until August 23 of that year. In an unsigned editorial accompanying a news story about the lynching of Emmet Divers, a Black man accused of raping and murdering a white farmer’s young wife, the newspaper offers a robust defense of the men who took the law into their own hands: “The Standard is opposed to mob law on general principles, but believes there are times when Judge Lynch might be called up without detriment to society when such a crime as that committed by Divers has been perpetrated and there is no doubt of the guilt of the person accused…. Husbands, fathers and brothers, of whatever race or color, can find much to palliate and excuse in the conduct of the infuriated men who lynched the brute, Divers, in Callaway county Thursday morning.” (“Savage” may have been a better word than “infuriated.” Divers was hanged twice, first from a bridge near Calwood, then from a telephone pole in Fulton after his corpse was riddled with bullets.)

Jacks, who died at the age of 76 on Dec. 5, 1921, is buried in the Montgomery City Cemetery. His son, Richmond Keith Jacks, sold the Standard in 1945. (Another son and a daughter left town as adults; a third son died young.)

Details about Jacks and his inflammatory letter, as most things, have largely slid into obscurity, though not forgotten. Just like an editorial published in The Woman’s Era in June 1895, a number of accounts, including an online history of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, get Jacks’ name wrong. “Journalism 1908: Birth of a Profession” — a book largely celebrating the founding of the nation’s first school of journalism at the University of Missouri — mentions Jacks’ “incendiary” letter briefly in a chapter on the African American press, calling it an attack on Wells-Barnett’s “character and morals in an effort to discredit her work, remove her British support, and stop her tour.” (Jacks’ letter actually did not refer to her.) “Self-Made,” the fictionalized biopic about Madam C.J. Walker, makes passing reference to Jacks, but does not name him, when the actress portraying Margaret Murray Washington says, “Oh, we started in what, 1895, when that awful man denigrated Negro womanhood in the Missouri newspaper” (season 1, episode 2). The Missouri Press Association has no record that it ever repudiated the letter sent by its former president.

* There were a few brief items about controversy. The Henry County Democrat of Clinton, for example, reported Jacks “recently stirred up a hornet’s nest by writing the Anti-Lynching League of England.” After the letter “got into print … every mail brings Mr. Jack (sic) letters and resolutions from indignant colored citizens of African descent.” Several newspapers published a paragraph about a Baptist association passing resolutions denouncing Jacks at a meeting in Mexico, Mo., but provided few details or context. The Topeka State Journal, for example, said Jacks was accused of writing “some very mean things about the colored race in this country in communication to the Anti-Lynching league of England.” (Originally published March 20, 2021)

© 2021 Roland Klose. All rights reserved.